Medieval art in Bologna

Updated on 14 November 2022 From Bologna Welcome

Massimo Medica, an art historian and university lecturer; since 2001 he has directed the Musei Civici d'Arte Antica in Bologna, working there since 1984. His areas of research and study focus on medieval and Renaissance art, the subject of numerous interventions and international exhibitions.

Visitors to Bologna cannot fail to be struck by the predominantly medieval soul evoked by some of its most important landmarks, an expression of the political and civic fervour experienced by the city at the time.

Even at the risk of appearing biased, it is precisely at the Civic Medieval Museum that the visitor can gain an initial insight into the life and culture of the city at the time when it was able to compete with the most important European capitals, thanks mainly to the presence of its university. This is also evidenced by the ancient sepulchral monuments of the first professors, known as arks. Worth noticing among these is the 1348 tomb of the great Giovanni di Andrea , depicted twice, as it was customary to do: as defunct on the lid and as lecturer addressing his students on the side, portrayed through the spontaneity of gestures and attitudes. As such, the sculptures vividly capture what must have been the life and activity of Europe's oldest university at the time.

The museum is also home to the large wrought copper statue of the much-discussed pontiff Boniface VIII, which certainly stands out for its hieratic appearance and the splendour of its extensive gilding. The statue, crafted by the Sienese goldsmith Manno di Bandino, was installed by the Bolognese on the façade of today's Palazzo d'Accursio. It is certainly an extraordinary work and symbol of the political power of this pope 'loved by few, hated by many and feared by all'.

Continuing towards Via Indipendenza, a stop at St Peter's Cathedral is a must. Significant evidence remains of the former temple, already established in the 10th and 11th centuries and rebuilt in the Modern Era. The vestiges of the 13th-century Lion's Gate and the large sculpted Crucifixion from 1170-1180, now on the high altar, are a precious reminder thereof. Perhaps not everyone knows that the crypt also houses some important ruins of the ancient cathedral portals found during the restoration of the bell tower. These 12th-century fragments belonged to the jambs of the three portals that would originally adorn the church façade, as evidenced by their iconography featuring figures of Telamons with vines, fantastic animals and scenes from the life of Jesus.

As you leave the cathedral, walk towards Piazza Maggiore to find yourself facing the great Basilica of San Petronio, whose construction began in the last decade of the 14th century. In his will, Bartolomeo Bolognini laid down precise instructions for the decoration of his family's chapel, the fourth on the left side, now boasting one of the city's finest art examples of the 15th century. The vast project is attributed to Giovanni da Modena and enriched with stories of the Magi and St. Petronius, topped by great scenes of Heaven and Hell, with punishments and tortures rendered in a most horrific manner, perhaps recalling the troubled situation the Church, riven by the Great Schism, was experiencing at the time.

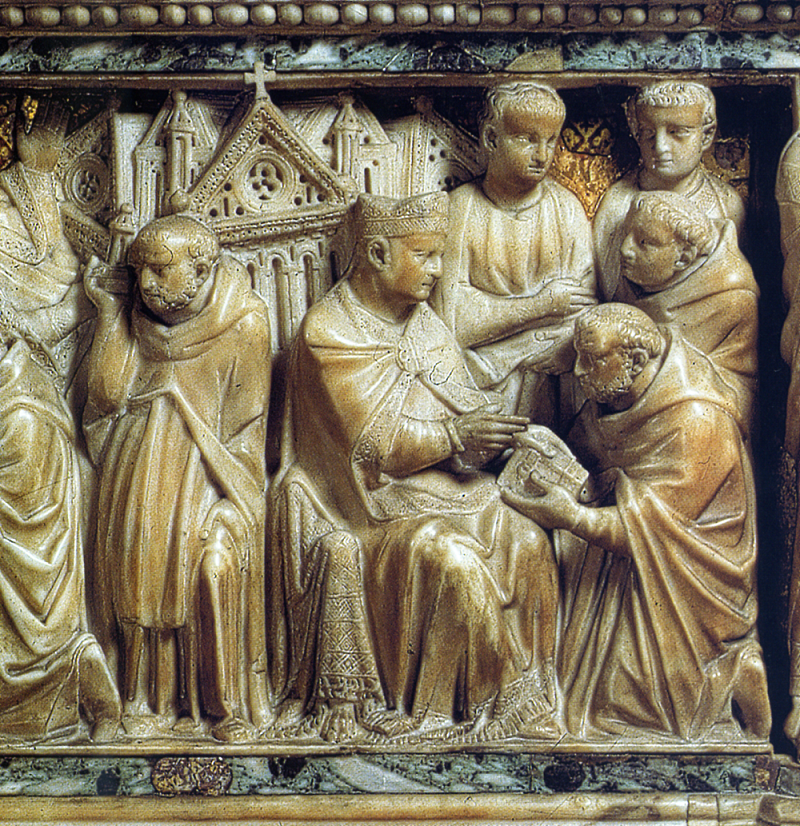

Not far from San Petronio is the Basilica of San Domenico, brimming with important artistic testimonies, the most valuable work being the marble Ark of the Saint, the result of the intervention of various artists who operated there over several centuries. The oldest part, completed in 1267 and consisting of the sarcophagus with stories of St. Dominic, is attributed to Nicola Pisano and his workshop. The highly original idea of this new monumental structure, a natural evolution of the reliquary-cases, masterpieces of goldsmith's art enshrining the saints' mortal remains, was to restore the preciousness by exploiting the luminous and subtle quality of Carrara marble, contrasting with the colourful glass backgrounds. Before the Renaissance and modern transformations, the ark resembled a sculpted sarcophagus, with clear classical reminiscences, supported by columns and figured supports, now acquired by various Italian and foreign museums.

As you leave San Domenico, I would recommend a visit to the equally marvelous Basilica of San Francesco, certainly one of the finest examples of the emerging Italian Gothic architecture. It is hard to believe that today's great altar and the surmounting marble altarpiece could have provoked a heated diatribe in its time between the commissioners, the Franciscans, and the two Venetian sculptors entrusted with its realisation, Jacobello and Pier Paolo Dalle Masegne. The work, which was actually completed mainly by Pier Paolo alone, was in fact rejected by the friars. Yet we are faced with an unprecedented and complex masterpiece, featuring an innovative, openly 'courtly' inclination of the depicted characters, rendered through that elegant flexuosity that anticipates certain later trends in Venetian painting.

After leaving the church and crossing the city along Via Ugo Bassi, Via Rizzoli and Strada Maggiore, we reach Palazzo Davia Bargellini, seat of the homonymous museum since 1920. Admittedly, it is no coincidence that the name of Bologna's most important painter of the 14th century, Vitale degli Equi, has been associated for centuries with the particular denomination "of the Madonnas", perhaps originating to endorse a devotional interpretation of his work, in reference to a specific production of the painter. Such would seemingly be confirmed by the so-called Madonna dei Denti (Madonna of the Teeth), one of the few dated works by the artist and one of the highest testimonies to the rich pictorial civilisation of 14th-century Bologna. The extreme elegance of the Virgin, garbed almost akin to a noble medieval lady, coexists with a more immediate sensitivity capable of expressing attitudes taken directly from daily life, resulting in an enjoyable and affectionate transposition of sacred themes.

It might not be known to everyone that around 1333-1334 the great painter Giotto visited Bologna to fresco the long-lost Cappella Magna of the Rocca di Galliera, built to temporarily house Pope John XXII during the Avignon Papacy. While no evidence remains of this glorious project, a signed Polyptych with the Virgin and Saints, now part of the Pinacoteca Nazionale, documents the artist's activity in the city. Indeed, it cannot be ruled out that this precious painting may also have originally belonged to the decorations of the destroyed Rocca, whose ruins can be admired today by the coach station. The castle also included another chapel allegedly dedicated to the Angels and Archangels, the same figures that appear on either side of the beautiful Virgin and Child in the polyptych.ù

© Pinacoteca Nazionale di Bologna

To round off the visit, I would suggest a walk outside the city along Via dell'Osservanza, up to the 19th-century Villa Aldini, built at the behest of Antonio Aldini, Napoleon's minister. On that occasion, the ancient round church of Madonna del Monte was incorporated into the architectural complex. Having survived the vicissitudes of time, when it was converted into a dining room, the circular structure still retains twelve niches with a precious pictorial cycle depicting the Apostles with books and scrolls. The decoration, concealed for generations and rediscovered in the 20th century, is today considered one of the rarest examples of late 12th-century Bolognese art. Besides this medieval marvel, the view of the city from the hill is certainly the best way to bid Bologna farewell.

Courtesy of Bologna Civic Museum